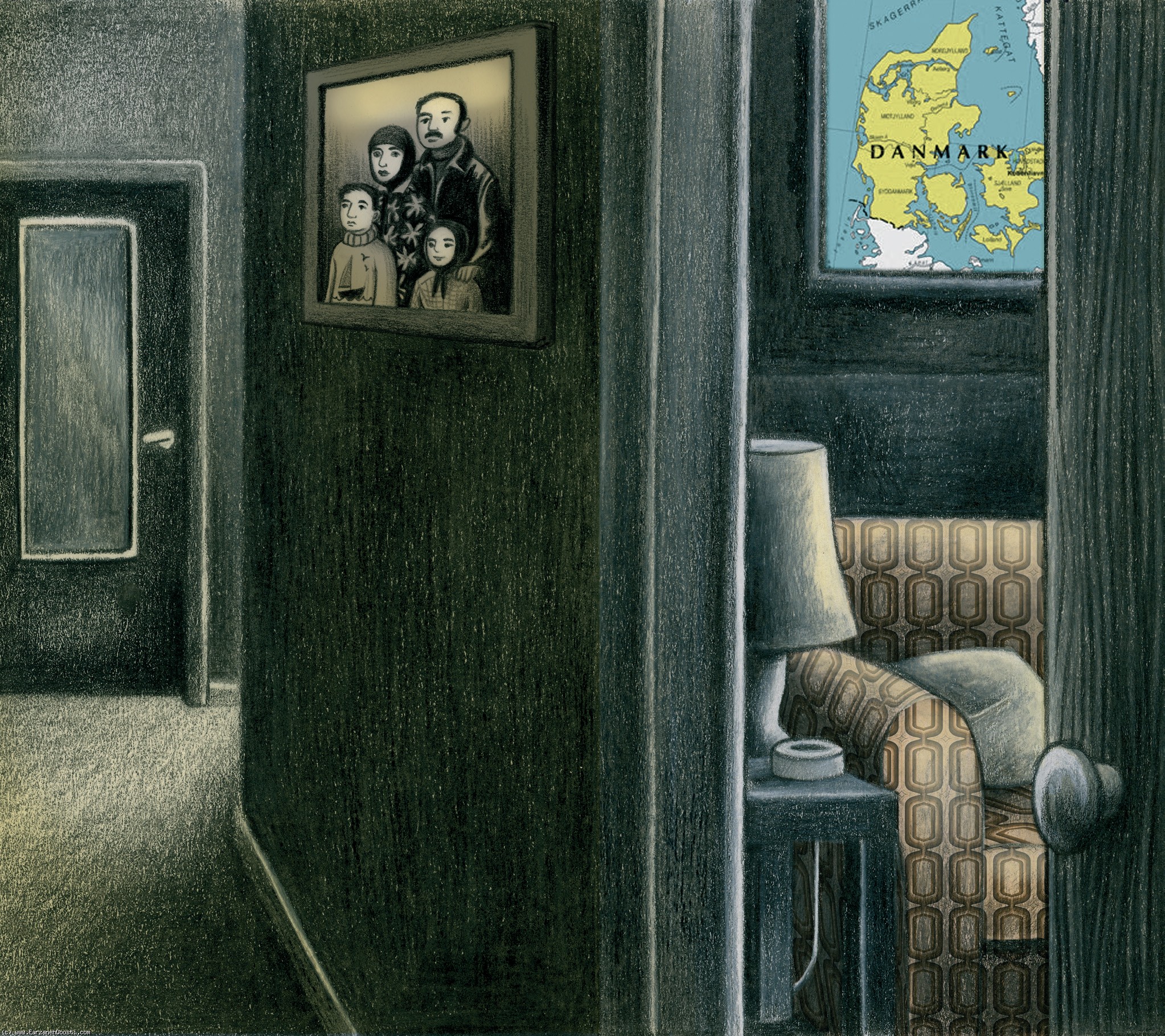

We lived in a house of closed doors. The door to the veranda was closed. The third room’s door was closed. The bifolding doors to the hall were closed–we had placed an American sofa in front of them. The door of the big bathroom was closed. The basement’s door was closed. The door of the toilet in the yard was closed. The door opening to the ridge roof was closed. And so was the door of the large hall all over the springs and falls and winters because we never had enough oil to heat up the whole place. Only in summers the doors opened and I could play ping pong with my mother with the ping pong table in there. She put a bedstead below my feet so that I could reach up the table and then she tried not to strike hard returns. My mother was Iranian Girls’ Schools Champion and fond of penhold grip of the racket, while I favored shakehand. We lived in a world in which people followed certain ideologies even for how to grip a racket, and from the very beginning I sided with the Western party.

Our styles were totally different. My mother used to hit short, tight topspins while my hits were rather long and loose. I was more at ease with sidespins while my mother made better topspins. Yet in spite of all the trophy cups Mother had received, I won because of my playing style — the victorious western style. Mother still followed Eastern methods, yet Father wanted to take us to Denmark, a place in the West that ironically paid living subsidies, unemployment compensation and allowance for the children like most socialist countries. And in order to convince my mother to leave, each day he locked up more and more doors of our house.

Like many other frivolities, my father’s wish to go to Denmark seemed a whimsical dream. Nights when my father bragged about his new discoveries of Danish government subsidies for gypsies and dissidents, as well as for the displaced and the unsupervised, Mother just kept silent, and agreed to come along with us to the Metropol Photographer’s to take a pass photo. In that photo Mother wears a small scarf and a long gown similar to a manteau–the term, however, was a new concept for ordinary women in the year 1983, women who were neither partisans nor did they belong to kamikaze Fadais or militant Hezbollah. She wears a crocheted shawl with large knitted flowers on her shoulders holding one angle in her fist. The three-year-old Sarah wears a babushka, a muffler and a bloated anorak. Pressing his arm against my mother’s, my father wears a closefitting turtleneck under his leather coat. I wear a woolen pullover marked by well-knitted shapes of a boat and two V-shaped birds flying in its sky. We were a family preparing for icebound Denmark.

Written by Mohammad Tolouei

Translated from the Persian by Farzaneh Doosti

Leave a Reply