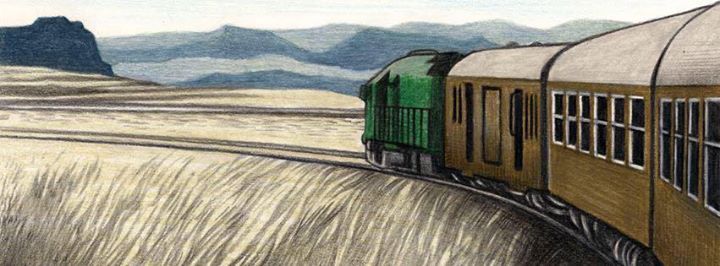

The Three-Twenty-Seven train from Tehran to Andimeshk left the station at 11.45 in the morning of July fifth, 1984, with my father in compartment number eight of its third car. My mother was not there to wave a handkerchief and cry, or to place a consoling hand on my head, or to hold up Sara to the window for a last kiss. We were in Rasht and living through one of those calm periods that followed an all-out row between my parents. My father had left for Tehran out of spite and boarded the Andimeshk train with the intention of going all the way to the frontlines to get himself killed in the process. However, somewhere along the way he had changed his mind about dying and accepted a volunteer post instead, teaching the school-age soldiers behind the front. He returned home after three months, thinner than ever, sporting a full beard, with military fatigues and a trove of war stories.

All those stories, however, would prove to be fabricated if the signature I found in the train I once took on my trip to Esfahan would turn out to be my father’s. I was shaving in the train’s bathroom in order to look clean before arrival. It was just past five in the morning, and a frail light was showing in the sky. It was also high time for full bladders to line up behind the door and fidget with the bathroom door handle. I lathered my face and turned my back to the mirror. I have a habit of not looking in the mirror when I am shaving—because every time I do look in the mirror, I end up cutting myself, even though I use one of those triple-blade Gillette razors that you could not cut your face with even if you tried. I had my back to the mirror and was facing the door. Every time the razor filled up with hair I would clean it under the tap and turn my back again on the mirror and go on shaving.

It was then that I saw the signature. It had been carved on the red paint that covered the fiberglass wall of the toilet, written in an unlikely corner that was so high up it gave the impression that the signer must have been a very tall man. Under the signature it said: Ziauddin, August 1984. The signature, too, seemed identical to my father’s. A drop of water cascaded down my wet hair onto my eyelid and made me squint. Yes, it was definitely my father’s signature. I was amused how he had managed to carve it as high up as he had. He must have climbed on the metal sink, and he must have carved it with the key to our first tiny apartment of Banisadr Housing Plan on Maryam Street.

I kept on shaving with my back to the mirror, but I did not take my eyes off the signature. It was a lop-sided signature, not straight and confident like his usual ones. He must have signed it while the train was moving. It would not have looked this way if he had signed it—having nothing better to do—while the train was stopped in one of the stations.

What was he doing on an Esfahan train in that summer while he was supposed to be teaching young soldiers behind the frontlines? I thought about dialing his number on my mobile and asking if he was in Esfahan in the summer of 84, but then it crossed my mind that this particular car could have been attached to any locomotive and travelled to any one of the many possible destinations. So I gathered up my shaving kit and left the bathroom. I did not call my father; I knew we would end up fighting over selling the family land. In my notebook I wrote Summer 84 and put a question mark next to it as a reminder for the time I would get back to Tehran.

When I told my father about the signature, he scratched his naked belly that was showing in between the buttons of his shirt, took a cushion from the sofa, lay down on the floor under the air conditioning and went to sleep. There was nothing unusual about his behavior. Even grandmother used to say that, “Ziaoddin, God bless him, is a pain in the ass.” If he had something that he knew you wanted to hear, he would make you pray for the swift release of death before he told you about it. The more enthusiasm I would show, the worse it would get. So I took a blanket and went to sleep near him in the hot and humid Rasht of July under the cool breeze of the air conditioner.

Two years later, when he had his hemorrhoid taken out in a Tehran hospital and was recovering in my apartment, he told me about it. He was lying on his stomach on the floor and slurping up through a straw the thin soup I had made for him. It had been a year—except for cursory hellos and goodbyes—that we were no longer on speaking terms. If we did have to say something to each other, we spoke as if talking to a third person. It was, in fact, to this third person that he told the story, and I must add that to this day I have not dared to tell my mother about it.

The English translation of “Summer ’84 } تابستان 63” written by Mohamamd Tolouei is published in Samovar is a quarterly special issue, of and about translated speculative fiction, of the American magazine Strange Horizons, You can read the full text here.

Leave a Reply